Scientists are using COVID-19 vaccine technologies to develop better vaccines against influenza viruses, including H5N1 bird flu. The research could make annual flu jabs much more effective.H5N1 bird flu cases have US authorities — and other nations monitoring its outbreak — on high alert.

More than 60 human H5N1 infections have been confirmed in the US, mostly among agricultural workers close to infected cattle and birds. At time of writing, more than 123 million poultry have been infected across all US states, in addition to 865 dairy herds.

Also Read | Harmful Chemicals Found in Plastic Cooking Utensils.

On Wednesday, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed the first "severe" case of H5N1 had hospitalized a person in Louisiana.

California governor Gavin Newsom also declared a state of emergency to address the spread of the virus.

Almost all cases of H5N1 in people are due to exposure to live or dead animals and no human-to-human transmission has been recorded.

To ensure readiness for potential transmission between people, scientists are testing new vaccine technologies to protect against emerging diseases.

New research may have found a breakthrough new method for creating more effective vaccines against influenza viruses.

The study, published December 19 in the journal Science, demonstrated a new way to improve the effectiveness of the annual flu shot.

Our immune systems are "biased" towards certain flu viruses

The new study aimed to understand why seasonal flu vaccine effectiveness is only between roughly 40-66%.

There are many strains of influenza circulating at any time and health authorities constantly monitor their spread to create targeted seasonal vaccines.

The final jab in the arm usually contains four selected flu strains, but the body rarely develops a good response to each.

Part of the problem is that people’s immune systems often produce antibodies tailored to a specific influenza subtype — not necessarily the specific ones put into the vaccine.

"For a long time, people thought that individual flu strain preference [subtype bias] was something you couldn’t do anything about," Mark Davis, an immunologist at Stanford University, US, who led the study.

But Davis’ team found the real reason for these immune biases — we inherit them our parents via our genes.

In an initial analysis of twins and newborns, around three-quarters of people with no previous exposure to influenza were found to have biased immune responses to specific flu strains.

Boosting seasonal flu shot effectiveness

Davis’ team then sought to "unbias" the immune system so it could respond better to different types of influenza strains.

Their new vaccine technology combines key molecules from different flu strains into a single compound.

The immune system recognizes its preferred molecule, then recruits other "helper" immune cells to build defenses to all strains in the combination.

Although only tested in lab dishes so far, Davis said their vaccine platform could push the effectiveness of flu vaccines from its around 66% "into the nineties."

The current flu vaccines don't give equal protection to all the influenza viruses it contains, so "you’ve got to make a vaccine that has all the major variables in it," Davis said.

New methods could improve flu vaccines

Isabelle Bekeredjian-Ding, director of the University of Marburg’s Institute for Medical Microbiology and Hospital Hygiene in Germany, said the research sheds light on "something that, at least in vaccinology, has not been fully understood."

“The real highlight of the paper is that it can describe the [immune] cell properties that are needed to produce specific types of immune responses," said Bekeredjian-Ding, who was not involved in the research.

A drawback of Davis’ study was that it was lab-based, meaning the vaccine has not yet been trialed in humans.

Davis said their next task is to convince manufacturers that adopting their method is the way for forward in vaccine development.

After that, the new vaccines will need to go through rigorous testing in clinical trials to ensure they are safe and effective. Only then can they become available for widespread use.

Testing COVID technologies to target H5N1

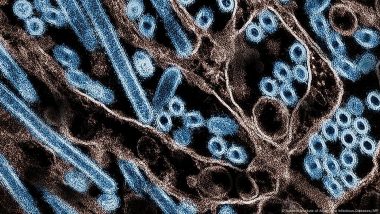

Meanwhile the CDC has completed a study of an H5N1 vaccine using the mRNA technology used to create COVID-19 vaccines.

The study, published in Science Translational Medicine, tested a prototype H5N1 mRNA vaccine in ferrets.

Vaccinated ferrets, even those with severe symptoms, overcame H5N1 infection, but unvaccinated ferrets did not.

The measure is a milestone in pre-pandemic preparation, said Bin Zhou at Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, USA, who led the study.

The vaccine is yet to be tested in humans, but Zhou thinks similar results could be expected in human trials.

“We can say that the mRNA is a promising platform… If there is a pandemic then we’re prepared for that part, unlike COVID-19 at the beginning where we didn’t have anything prepared for the vaccine,” Zhou said.

Edited by: Fred Schwaller

Sources

Coupling antigens from multiple subtypes of influenza can broaden antibody and T cell responses. Published by Vamsee Mallajosyula, Saborni Chakraborty et al. in Science. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.adi2396

An influenza mRNA vaccine protects ferrets from lethal infection with highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus. Published by Masato Hatta, Yasuko Hatta et al in Science Translational Medicine. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.ads1273

(The above story first appeared on LatestLY on Dec 20, 2024 01:20 AM IST. For more news and updates on politics, world, sports, entertainment and lifestyle, log on to our website latestly.com).

Quickly

Quickly